Max Scheler once wrote, "There never was and is not now a "Christian philosophy," unless one understands by this an essentially Greek philosophy with Christian ornamentation" ("Liebe und Erkenntnis" ("Love and Knowledge") Gesammelte Werke 6).

Perhaps this quite provocative statement can also be applied to a so-called "Christian anthropology," for it is nothing more than a Greek anthropology with Christian embellishments.

Namely, a Greek body-soul paradigm defined as “rational animal” conveniently adorned by "

imago Dei."

But I suppose I should give some evidence for my near blasphemous remarks. I am not necessarily criticizing the body-soul paradigm itself, but only its literalized form seemingly to have arisen from the demythologizing tendency in Aristotle (which was inherited for the most part by the Thomistic tradition) and the radicalizing of that demythologization, by Descartes. The former having literalized the symbol once expressed by Platonic tradition (which was inherited for the most part by the early Church Fathers) and the latter having separated this literalized paradigm into a dualism. This literalization has obscured the awareness of how the Greek anthropological paradigm of body and soul arose from an archaic myth, that of Orphism, and how St. Paul and the early Christians adopted this anthropological paradigm under its thoroughly symbolic form. The direct result of this literalization, then, is the unfortunate, but ever common conception that the "body," or to use the Pauline terminology, "flesh," is

literally the locus of evil.

This argument, more or less, is one advanced by Paul Ricoeur in,

The Symbolism of Evil. His insight is astonishing! Yet so calmly clarified, as if it were common knowledge. In fact, it is a treasure tucked away toward the end of his work; but an excellent observation I think so many today, especially Christians, could benefit from. There are two elements to his argument which reveal the current misunderstanding of this ancient anthropological paradigm and its relation to Christianity.

The first I have only implied above, which is that this conception of a human person as constitutive of body and soul was

not inherited by the first Christians from their Jewish tradition or background, and therefore, neither from their Scriptures, i.e., from the Genesis story of creation, which Ricoeur calls the "Adamic Myth." Rather, the anthropology of the Adamic myth is essentially "monistic," whereby, there is no distinction between two elements in man: a body and a soul. Indeed, Ricoeur, in his chapter on the Orphic myth of the "exiled soul," states:

None of the other myths [which includes the Adamic myth] is a myth of the 'soul'; even when they speak of a rupture in the condition of the human being, they never divide man into two realities. ... [Indeed], no myth is fundamentally less 'psychic' than the Biblical myth of the fall. It is, of course, and anthropological myth, and even the anthropological myth par excellence, the only one, perhaps, that expressly makes man the origin (or the co-origin) of evil; but it is not in any degree a myth of the adventures of the 'soul' considered as a separate entity. On the contrary, it is a myth of the 'flesh,' of the undivided existence of man(SOE, 280-81).

If this rupture was never indicated by the Biblical myth of the fall, how then do we explain the rupture of the human person, the tension which arose between the body and soul, with the loss of "original justice," that the

Catechism of the Catholic Church tells us was a consequence of the fall.

The harmony in which they had found themselves, thanks to original justice, is now destroyed: the control of the soul's spiritual faculties over the body is shattered, the union of man and woman becomes subject to tensions.... Harmony with creation is broken.... Death makes its entrance into human history"(CCC, 400).

Strange, is it not? The last three of the four ruptures are specifically indicated in the Genesis account and are cited in the passage accordingly, but the first is not specified nor cited! So where did this dualistic paradigm of body and soul come from? Why so much emphasis on the body-soul paradigm if it never was explicit in Scripture, whereas the symbol of the "image of God," in fact was made explicit, but which has become, to a large extent, the subordinate aspect?

The answer in obvious: from Greek philosophy. But this is still not quite accurate, for the paradigm originated in what Ricoeur calls "the myth of the exiled soul," i.e., the ancient myth of Orpheus, where the body (

soma) is identified with a prison (

sema). The soul then, while in the body, is in a state of exile, and man is composed of two elements: an evil element which is the body, and a divine element, the soul.

So, these ideas which are commonly attributed to either Plato or gnosticism actually have their origins before both.

Now, Plato cannot be interpreted as holding to Orphic dualism, in the strict sense, even though

he used this dualistic paradigm in his writings. The meanings are obscured now due to a literalization of the paradigm that would entice such a reading, but the reason that Plato is not a dualist in the Orphic sense, which is the same reason the early Christians are not who adopted this paradigm, is because both properly understood the

symbolism of the body! And this is Ricoeur's second point: the literal 'body' or 'flesh' is not the place of evil nor an evil thing, but 'body' is only a

symbol for an element of evil in the soul itself, viz., "the seat of everything that happens to me without my doing"(SOE, 332). Body only symbolizes an involuntary element in the soul itself, and thus gives us an understanding that evil is something that the soul inflicts upon itself as opposed to that which the body inflicts upon the soul. This is clear in Plato's

Phaedrus with the metaphor of the Charioteer, upon which I adopted for the title of my blog. See my post, "'The Charioteer': Source, Meaning and Significance."

Ricoeur himself, of course, puts it best:

... for the body itself is not only the literal body, so to speak, but also a symbolic body. It is the seat of everything that happens in me without my doing (SOE, 332).

... the Pauline concept of the 'flesh' and the 'body' designates not a substantial reality, but an existential category, which not only covers the whole field of passions, but includes the moralizing will that boasts in the law. It is the alienated self as a whole, in opposition to the 'desires of the Spirit,' which constitute the inward man (SOE, 333).

The explanation of evil by the body is not an objective explanation, but an etiological myth; that is to say, it is ultimately a symbol of the second degree. But if that explanation aims at becoming scientific, as in modern times, then the ethical character of evil action disappears; man cannot impute evil to himself and at the same time refer it to the body, without treating treating the body as a symbol of certain aspects of the experience of evil that he confesses. The symbolic transmutation of the body is a necessary condition for its belonging the mythics of evil (SOE, 336; my emphasis).

Ricoeur finally asserts that this anthropological paradigm of body and soul can be seen as compatible with the Adamic myth of the fall

only if the symbol is properly and duly recognized. In other words, only when the body-soul paradigm is seen in its symbolic (and not literalized) form, can it be compatible with Scripture.

However, it seems that the kind of paradigm held today, in our neo-Thomistic, post-Cartesian atmosphere of the Church and modern world respectively, in light, also, of the scientific revolution and the Enlightenment in our recent western history, has moved away from this kind of symbolic understanding. So to put it bluntly, yes, I am saying I think our current so-called "Christian anthropology" is not a Christian anthropology at all, for it is not compatible with the creation story of Genesis. Though, at the same time, I am affirming that those elements of the New Testament, in St. Paul's writings, have sufficiently retained the symbol and are therefore in no way incompatible with the Old Testament.

In light of all this, Max Scheler's statement cited above holds great truth.

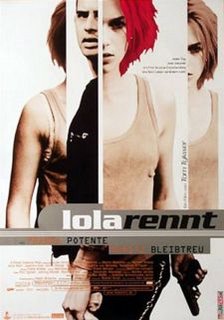

Who ever said Germans couldn't make movies? Granted, German films are not all that common, the film, Run Lola Run (1998), directed by Tom Tykwer, is an excellent film that gives Germans a name for themselves in film. Tykwer has directed a number of films since this one, his most recent being the movie currently in theaters, Perfume: The Story of a Murderer, as well as Ich Dich Auch, also in 2006.

Who ever said Germans couldn't make movies? Granted, German films are not all that common, the film, Run Lola Run (1998), directed by Tom Tykwer, is an excellent film that gives Germans a name for themselves in film. Tykwer has directed a number of films since this one, his most recent being the movie currently in theaters, Perfume: The Story of a Murderer, as well as Ich Dich Auch, also in 2006. process of trying to obtain the money is repeated three times, each time showing how the different actions on Lola's part play out both in the future lives, and the immediate circumstances, of those she encounters.

process of trying to obtain the money is repeated three times, each time showing how the different actions on Lola's part play out both in the future lives, and the immediate circumstances, of those she encounters.